Those of us who reside on the east coast are fortunate enough to not have to face forest fires or their associated hazards on a routine basis. Scenes of smoke-filled skies and fire crews working around the clock to snuff out flames might be common in Mediterranean California, but for us east coast dwellers, scary sights like this are only seen on our television and cellphone screens from the comfort of our homes.

That’s what made the week of June 4-9ᵗʰ very unusual in the northeast. Forest fires burning in Quebec sent plumes of smoke south into New England and Mid-Atlantic, blanketing the sky over densely populated areas with thick orange haze, resembling imagery akin to a disaster film.

The smoke was so thick that New York City registered the worst air quality of any major city in the world on June 7ᵗʰ, and it’s a no brainer as to why from the header image above. It was the worst air quality that the northeastern United States had observed in at least 50-years. One can’t be faulted for being alarmed, or at the very least, caught off-guard by the undiluted veil of smoke.

As usual, a flurry of politicians, journalists and environmental activists began blaming the fires on [sigh…] human-caused climate change. Indeed, Canadian Prime Minister, Justin Trudeau Tweeted that “We’re seeing more and more of these fires because of climate change.” If he bothered to do any research, the Canadian government’s own data begs to differ with that assertion, but we will dive into the nuts and bolts later.

Considering that wildfires negatively impact both human life and property, it’s easy to speculate that people are given the impression forest fires are unnatural in occurrence and must be put out or all-out prevented. Compounding this mindset is the idea that before humans came along and meddled with the climate, nature was in perfect harmony with itself. It was all sunshine and rainbows. Yet, neither of these mindsets reflect reality.

The Facts

Humans, for whatever reason, like to locate themselves in fire-prone regions and we often engage in activities that—intentionally or not—ignite fires.

Every spring in boreal forests (such as in central and southern Quebec), there’s a small window of opportunity where dead vegetation leftover from the previous year can dry out sufficiently enough, that if there is an ignition source, such as lightning or human activity, an uncontained fire can multiply its burn area on the turn of a dime placing countless lives and property in danger.

Yet, in a natural sense, forest fires are essential for maintaining the overall health of forest ecosystems. Positive aspects of fires include, but are not limited to:

- Clearing out fallen trees, dead vegetation and underbrush allowing sunlight to reach the forest floor and penetrate the top layer of soil to stimulate new plant growth.¹

- Nutrients stored in plants are released when vegetation burns, enriching the soil’s fertility (i.e., nutrient cycling). This too, stimulates plant growth.

- Select tree species, such as the lodgepole and jack pine, reproduce from the dispersal of seeds stored in their cones. If exposed to heat from a wildfire, the cones may open, setting the seeds free.¹

- Fires are known to act as a natural form of pest control. They kill off invasive insects and parasites that can damage certain tree species.

These two starkly contrasting impacts make fire a rather challenging policy issue that is central to not only forest management, but also emergency preparedness and [climate change] mitigation.

The Meteorology

Headlines and armchair experts articulated with boastful confidence that the primary cause of the Canadian fires, and in particular the smoke plumes advected southward into the northeast, was climate change. Despite the fact these claims are neither supported by the greater body of peer-reviewed work nor the observational record, all that is needed here is a satisfactory meteorological explanation.

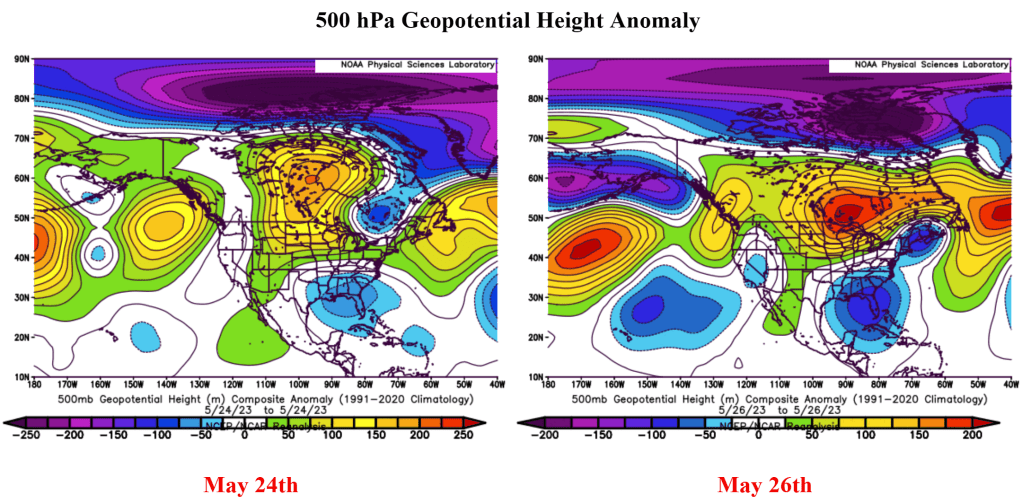

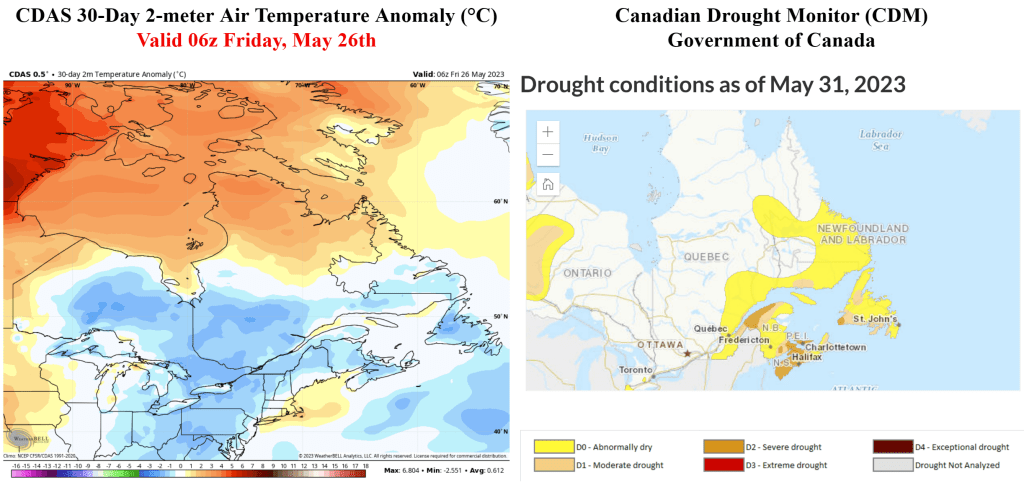

Fires, of course, are fueled by an environment that is characterized by persistently warm weather, dry soil and gusty wind. An enormous blocking high-pressure ridge began to build over central Canada on May 24ᵗʰ (Figure 1a) before expanding and moving over Ontario and Quebec by the 26ᵗʰ (Figure 1b) where it remained through the first week of June.² Beneath the ridge, downward motion on the synoptic scale forced air to sink, dry and warm by adiabatic compression over a period of several days, creating favorable fire weather conditions that had previously not been in place.

Prior to this, temperatures were near to slightly below average across Ontario and Quebec (Figure 2a) and as of the latest update from May 31ˢᵗ, Quebec isn’t even in drought (Figure 2b).³ This justifies the case that the fire weather conditions were a transient response to ongoing weather conditions which primed the environment, not a long-term pattern that could be altered by the climatic base state.

Once the light grasses and vegetation had been dried out, the forests quite literally became a tinderbox. One spark from an ignition source was all that was required to set the forest ablaze. This came on June 2ⁿᵈ as hundreds of lightning strikes from a passing low-pressure system struck the dry vegetation, igniting numerous fires within a short span of time.

With the fires seemingly starting simultaneously, it gave many social media users the impression that the fires were set by arsonists [Author’s note: I too, had previously thought arson was to blame, but it turns out I was incorrect]. Some conspiracy theorists even went as far as to entertain the idea that the Canadian government intentionally set the fires, but such fringe claims are demonstrably false. “Back lighting” is a firefighting technique whereby a fire is intentionally started ahead of an active front to consume some of the fuel, creating what is analogous to a belt that prohibits a wildfire from spreading.

As the low-pressure system pivoted east and stalled off the New England coastline, the cyclonic wind flow stoked the fires, and in the process stirred up an abundance of tiny smoke particulates and advected them downwind into the northeastern United States resulting in hazy skies that led to a sharp reduction in air quality. As the low intensified as the week wore on, it set up a feedback loop which further deteriorated air quality to the point the skies were covered in a thick orange haze. It reached its pinnacle from June 5-7ᵗʰ before gradually thinning out.

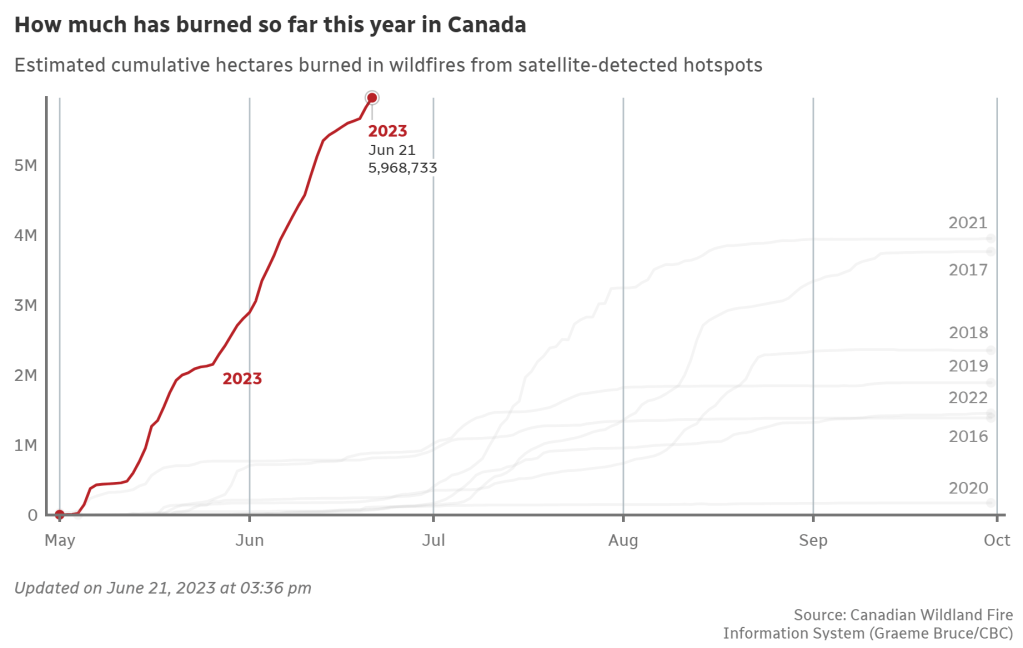

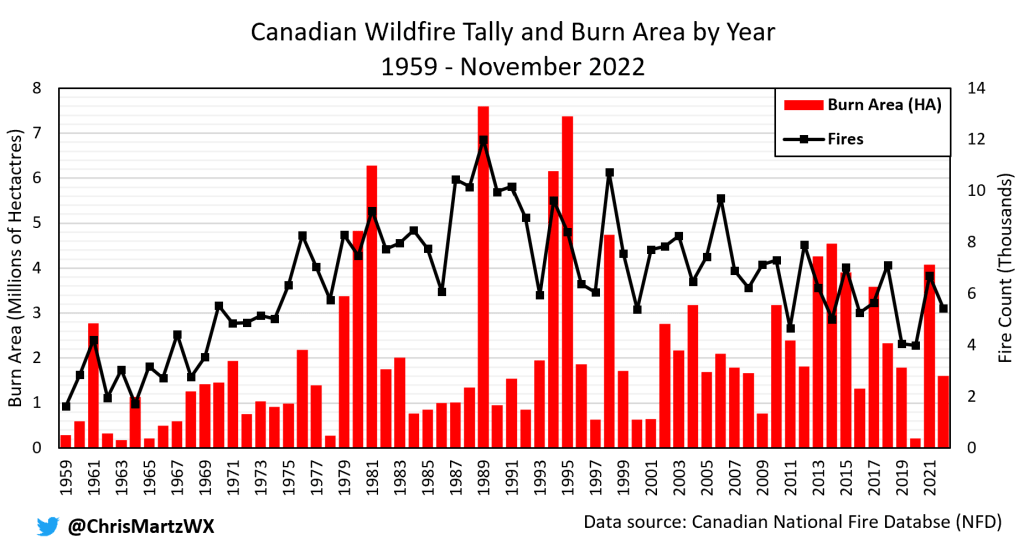

As of June 21ˢᵗ, roughly six million hectares of land has been scorched by the fires across Canada (Figure 3).⁴ While year-to-date burn area statistics only date back to 2003, total burn area by year has been available in the National Fire Database since 1959.⁵ Of the 64-years available (that includes 1959), the year-to-date burn area has surpassed 60 of them. Without a doubt, this has been an unmatched start to the Canadian fire season within the period of record [which one must keep in mind has only been in the fire suppression era and is narrow in temporal scope].

Did Climate Change Play a Role?

The begging question that now remains is did climate change play a role in the fires and the overabundance of smoke that blanketed the skies over the northeast, and if so, to what extent?

Several climate scientists at the forefront of the issue made no bones, and without hesitation, immediately jumped on the activist bandwagon to do the usual finger-pointing at Big Oil without doing any actual research, let alone developing a research question to ponder on.

The first thing a responsible scientist would do in this situation is to check Chapters 11 and 12 of the United Nations’ IPCC AR6 WG1 report to see what the general body of peer-reviewed scientific literature has to say on the question at hand.⁶ ⁷ As Dr. Roger Pielke, Jr. argues, the IPCC isn’t immune from error, nor does it always detail trends in specific regions, but it is a great place to embark on a quest to find answers to the question at hand.

I was surprised to find that the IPCC does not thoroughly assess trends in wildfires, but instead puts intent focus on fire weather—that is, weather conditions that are conducive to both triggering and sustaining wildland fires (i.e., defined as compound hot, dry and windy events).

Some of the key findings from AR6 include:

- “There is medium confidence that weather conditions that promote wildfires have become more probable in southern Europe, northern Eurasia, the USA, and Australia over the last century.” — Chapter 11, Section 8.3

- “[There is] High confidence that fire weather, (i.e., compound hot, dry and windy events), will become more frequent in SOME regions at higher levels of global warming.” — Chapter 11, Table 11.2

- “Between 1979 and 2013… the mean length of the fire season increased by 19% (Jolly et al., 2015). However, at the global scale, the total burned area has been decreasing between 1998 and 2015 due to human activities mostly related to changes in land use (Andela et al., 2017). — Chapter 11, Section 8.3

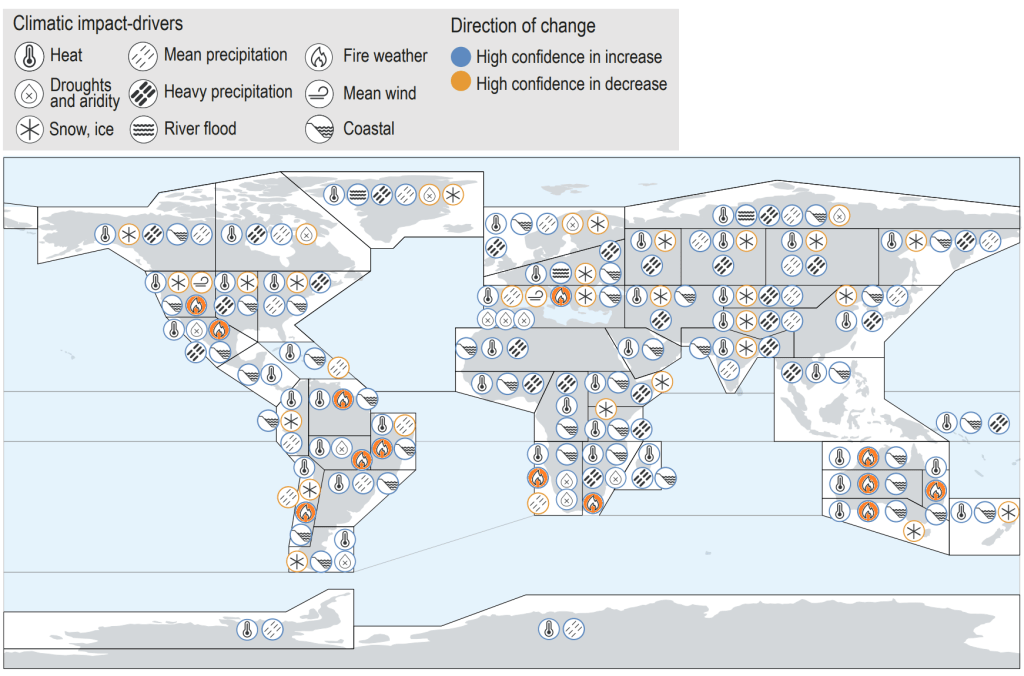

In Chapter 12,⁷ the IPCC provides a detailed infographic which conveys the projected change in certain climatic parameters with high confidence by 2050. Variables which are circled in blue indicate projected increases, and variables that are circumscribed in orange indicate projected decreases. I took the liberty to color in orange where fire weather is projected to increase [with high confidence] by 2050 in Figure 4 below.

I want to direct your attention to eastern North America. Notice there is no fire icon, meaning fire weather is neither projected to increase nor decrease in Quebec over the next few decades.

While I normally could care less about future projections, as most climate models exceedingly fail at matching physical observations, these findings are important because they stand sharply at odds with what climate activists claim “the science” says. What this suggests is that most don’t actually read much into the literature, but instead parrot talking points from a handful of academics (e.g., here and here).

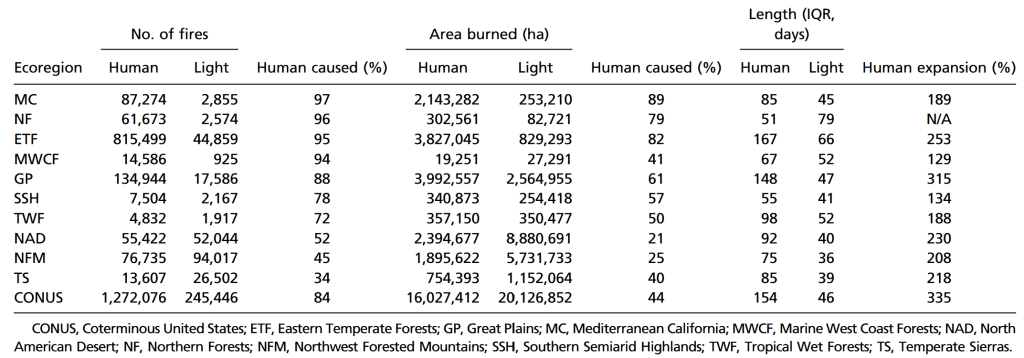

It should go without saying that wildfires require more than a favorable environment to combust. There must also be an ignition source and fuel. Natural fires are typically started by lightning, but an overwhelming majority stem from human activity. According to Balch et al. (2017), 84% of wildfires in the Contiguous United States during the period 1992 to 2012 were started by humans (Table 1).⁸ In California, this number is over 80% (e.g., Balch et al., 2017; Chen and Jin, 2022).⁸ ⁹

So, what about the number of fires or amount of land area burned? Surely, there is an increase there, right? Well, no.

The Canadian government has kept high-quality data on fire count and burn area by the hectare since 1959 in their National Fire Database (Figure 5).⁴ The total number of fires increased until they peaked in 1989 at 12,015; since then, fire counts have decreased along a steeply negative trend. As far as burn area is concerned, there has been no measurable increase since the late-1970s. Interestingly enough, 2020 registered the fewest fire count in 51-years and finished with the lowest burn area since 1965. I must have missed the headlines on that.

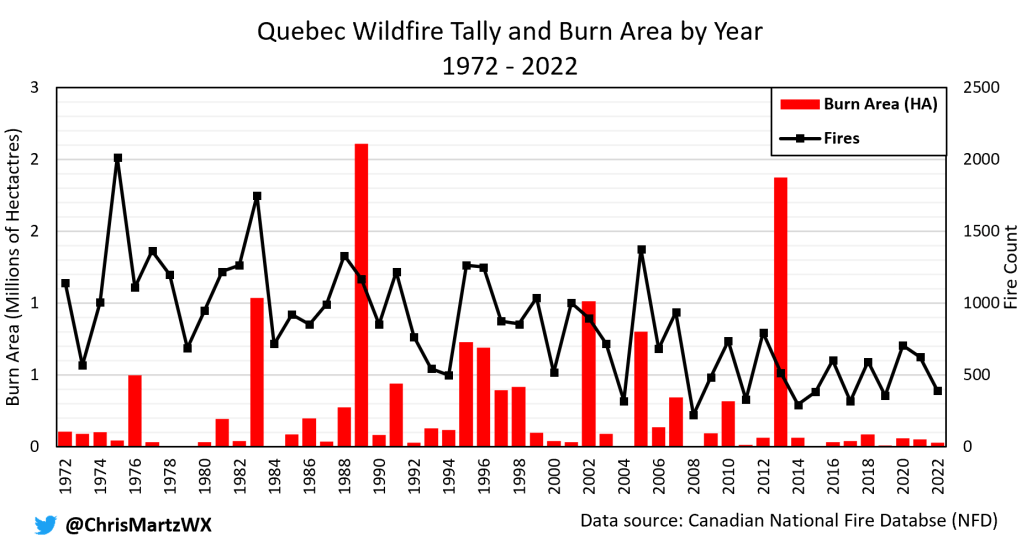

This trend is also evident in Quebec (Figure 6).

The overall decrease in fire count is mostly an artifact of the advancements made in firefighting capabilities, as well as the adoption of strict fire suppression policies. So, even if fire weather has increased in Quebec [which is not argued by the IPCC] as a result of man-made global warming, it has had negligible impact on the behavior of Canadian forest fires, suggesting that climate change isn’t the dominant player.

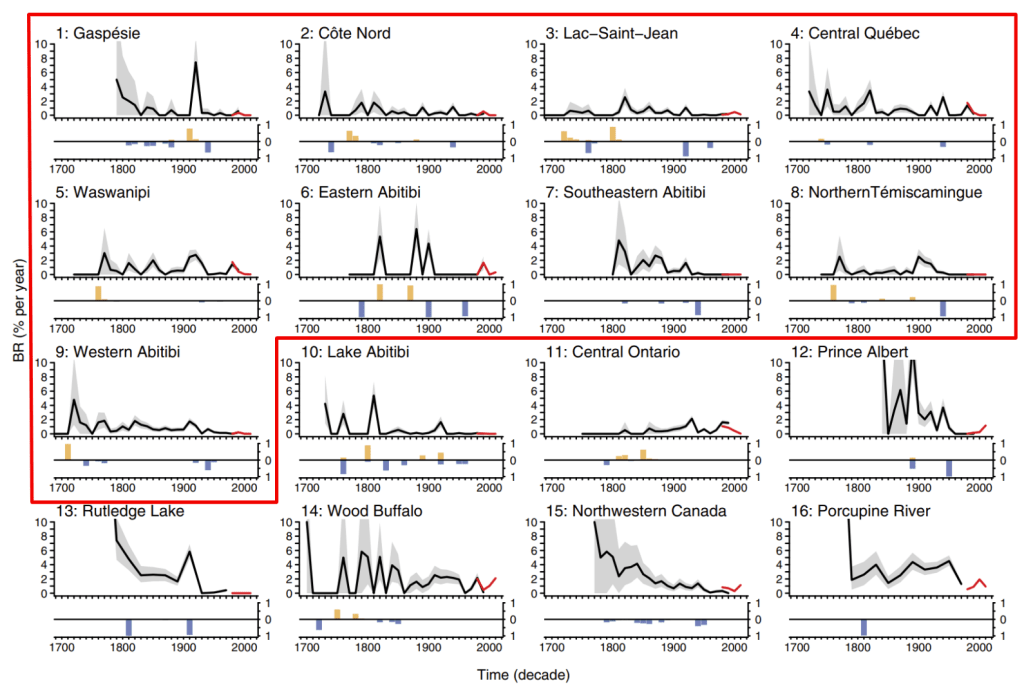

Chavardès et al. (2022) examined the burn rates in North American boreal forests at 16 historical sites, nine of which are located in Quebec, over a much longer period spanning from 1700 to 1990 (Figure 7).¹⁰ From this data, it is evident that burn rates in boreal forests across Quebec have been lower in recent decades than they were in the pre-industrial climate.

As for the ominous-looking orange haze that resulted from plumes of smoke drifting south on northwest flow behind a stalled low-pressure system, climate change had absolutely nothing to do with that.

The blocking high which promoted the favorable fire weather conditions formed due to anticyclonic wave-breaking, and then linked over the top, causing the low to stall off the New England coastline for several days until a kicker in the jet stream would get the ball rolling again. While high-amplitude Rossby wave patterns are infrequent during the warm season, they do happen from time to time.

While some scientists argue that high-amplitude jet stream configurations are to be expected with increased global warming, physical observations show no such trend (e.g., Blackport and Screen, 2020) and a grasp on basic synoptic meteorology finds the holes in that theory (I explain why here).

The incidence of fire and an upper-level air pattern that transported the smoke into the northeastern United States and depleted the air quality over densely populated areas was the result of random chance in a chaotic, non-linear, dynamic system, and more than anything, unfortunate timing. Throughout history, very similar events have occurred, such as “New England’s Dark Day” on May 19, 1780 when fires burning in Ontario blanketed the New England skies in a thick layer of smoke, causing many to think it was the end of times. The May 18, 1870 Saguenay fire spread smoke all the way to the British Isles. More recently, the 1950 Chinchaga fire in British Columbia and Alberta caused the sun to become dimmed or blacked out from Ontario down to Pennsylvania on September 24ᵗʰ; it became known as Black Sunday.

Final Remarks

In spite of the fact that there has been no observed increase in neither fire count nor burn area in Quebec, we are becoming more vulnerable to wildfire risks because we continue to develop residential areas and commercial districts in fire-prone regions.

In addition, many of the aggressive fire suppression policies that were implemented during the early 20ᵗʰ century have been strongly linked to the increase in woodland and bush fire burn area, particularly in the western United States and Australia. The removal of fire from healthy forest ecosystems allows dead trees and underbrush to accumulate on the forest floor, increasing the fuel load. This has led to an increased risk for larger and unstoppable fires.

Some experts argue that the best course of action to manage wildfire risk in the future is to rapidly decarbonize our global economy, but the evidence presented above is clear that the atmospheric carbon dioxide level has very little influence on wildfire activity. The best approach to policy would be to stop building infrastructure in regions susceptible to fire and to better our forest management practices, and in particular on federally owned lands. Sitting on our hands and blaming climate change for every abnormal environmental event is a waste of time when our efforts would be better spent on addressing how to manage risk and mitigate vulnerabilities.

References

[1] “Why Forests Need Fires, Insects and Diseases.” Government of Canada. June 22, 2023. https://natural-resources.canada.ca/our-natural-resources/forests/wildland-fires-insects-disturbances/why-forests-need-fires-insects-and-diseases/13081.

[2] “Daily Mean Composites.” NOAA Physical Sciences Laboratory. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://psl.noaa.gov/data/composites/day/.

[3] “Canadian Drought Monitor.” Government of Canada. May 31, 2023. https://agriculture.canada.ca/en/agricultural-production/weather/canadian-drought-monitor.

[4] Bruce, Graeme. “Canada’s Wildfires: Where They Are, how Much Has Burned and how It’s Changing Air Quality.” CBC. June 9, 2023. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/canada-fires-map-air-quality-1.6871563.

[5] “Canada Wildfire Information System.” Natural Resources Canada. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://cwfis.cfs.nrcan.gc.ca/datamart/download/nfdbpnt.

[6] Seneviratne, S.I., X. Zhang, M. Adnan, W. Badi, C. Dereczynski, A. Di Luca, S. Ghosh, I. Iskandar, J. Kossin, S. Lewis, F. Otto, I. Pinto, M. Satoh, S.M. Vicente-Serrano, M. Wehner, and B. Zhou, 2021: Weather and Climate Extreme Events in a Changing Climate. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change[Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M.I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J.B.R. Matthews, T.K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, pp. 1513–1766, doi: 10.1017/9781009157896.013.

[7] Ranasinghe, R., A.C. Ruane, R. Vautard, N. Arnell, E. Coppola, F.A. Cruz, S. Dessai, A.S. Islam, M. Rahimi, D. Ruiz Carrascal, J. Sillmann, M.B. Sylla, C. Tebaldi, W. Wang, and R. Zaaboul, 2021: Climate Change Information for Regional Impact and for Risk Assessment. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M.I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J.B.R. Matthews, T.K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, pp. 1767–1926, doi: 10.1017/9781009157896.014.

[8] Balch, Jennifer K., et al. “Human-Started Wildfires Expand the Fire Niche across the United States.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 114, no. 11, 2017, pp. 2946–2951, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1617394114.

[9] Chen, Bin, and Yufang Jin. “Spatial Patterns and Drivers for Wildfire Ignitions in California.” Environmental Research Letters, vol. 17, no. 5, 2022, p. 055004, https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ac60da.

[10] Chavardès Raphaël D., Danneyrolles Victor, Portier Jeanne, Girardin Martin P., Gaboriau Dorian M., Gauthier Sylvie, Drobyshev Igor, Cyr Dominic, Wallenius Tuomo, Bergeron Yves (2022) Converging and diverging burn rates in North American boreal forests from the Little Ice Age to the present. International Journal of Wildland Fire 31, 1184-1193. https://doi.org/10.1071/WF22090.

[11] Blackport, Russell, and James A. Screen. “Insignificant Effect of Arctic Amplification on the Amplitude of Midlatitude Atmospheric Waves.” Science Advances, vol. 6, no. 8, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aay2880.

Categories: Climate

Hi Chris

I tried to post this on your blog, but it would not accept. In any case here it is

“ Hi Chris – With respect to your assumption that forest fires do no occur in the eastern USA, that is essentially true now. But earlier in the last century it was not.

See discussion of this in

Pielke, R.A., 1981: The distribution of spruce in west-central Virginia before lumbering. Castanea, The Journal of the Southern Appalachian Botanical Club, Sept., 201-216. http://pielkeclimatesci.wordpress.com/files/2009/09/r-23.pdf”

Best Wishes

Roger Sr

LikeLike

Hi Roger, it’s great to hear from you. I have missed our conversations on Twitter; it was always a highly educational experience.

My original statement pertained [of course] to the modern era, but I’ll admit that I didn’t realize how widespread fires were in the east back then. Thanks for the link. I’ll have a read.

Best regards,

Chris

LikeLike

Great work Chris!

LikeLike

Thanks Don!

LikeLike

Excellent analysis, thank you for all the effort.

LikeLike

Thanks Blair! Appreciate the feedback.

LikeLike

Excellent analysis; could I please translate it into Czech and use the pictures for a (non-profit) blog?

LikeLike

Yes, you may.

LikeLike

You’re leaving out the impact of the unrestricted logging and accumulated garbage ie cuttings and dried-out lumber fuel left behind.

The result has been burning and ecological damage never previously experienced. The wildfires of Australia are estimated to have killed in excess of over a billion animals and wiped out some species entirely. The famous Australian Koala was reduced to a fraction of its previous population. I am hard put to buy in to this sunny assessment you’re promoting

LikeLike

Hi Chris, thank you for your hard work.

last summer we spent three months camping in the Canadian Rockies. Banff, Lake Louise and Jasper nation park. It is a beautiful area. Driving north from Banff up the Ice Field Parkway, you could not help but notice all the dead trees on the mountain sides. In some areas about 2/3rds of all the trees on the entire mountain were dead. This is due to pine bore Beatles killing them. I do not know what Canadian policy is regarding forest management (removing dead timber, beatle spraying etc.) but there are all just waiting for a lightning strike to start a fire. In fact while we were staying in Jasper there was a lightning strike which did start a fire. It quickly became a problem and we were put on notice to be ready to evacuate. Fortunately the wind changed direction and they managed to get it under control and put it out after a week of fighting it. The dead trees still stand. Waiting for the next strike and providing food for the spread of the Beatles, perpetuating the problem. Maybe leaving the dead trees burn may be better management practice (stop the spread of the Beatles).

keep up the good work.

Ed

LikeLike

Just found your site , I like to educate myself , I’m not a smart guy but I read all the hoopla about climate change I know is false just from my schooling in the 70’s but this stuf about forest fires was very interesting because here in Alberta we always have said the management of the forest is gonna mess us up and it just did that this week in Jasper , they should’ve did a controlled burn long time ago to get rid of dead trees from the beetle infestation . Mike

LikeLike